“Authors aren’t the only ‘agents of meaning’ in the literary process,” he said. “Publishers, manufacturers, bookstores, agents, readers, and MFA programs all have influence on how texts reach readers, and, by extension, what kind of texts authors produce.”

In the belly of Amazon.com’s digital publishing empire, there is a cryptic requirement for authors using Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP), a self-publishing service. Authors may publish almost anything they want, as long as they follow this rule: “We do not allow content that disappoints our customers.”

What is disappointing content?

A list of answers includes content that is primarily advertising, content that is too short, and “content that does not provide an enjoyable reading experience.”

Never mind that Amazon’s definition of “disappointing” is circular, ambiguous, and probably unenforceable. The company’s growing dominance in the book publishing industry, combined with its relentless focus on customer service, may be reshaping the course of literary history, according to Mark McGurl, Professor of English at Stanford University.

He made this argument at the University of Washington at Scale & Value: New and Digital Approaches to Literary History, a May 2015 gathering of prominent literary scholars responding to the explosion of digital humanities research. The event was sponsored by the Simpson Center for the Humanities and Modern Language Quarterly, which will publish a special issue based on the conference. Speakers explored both how questions (about computational methods for literary analysis) and why questions (what is all this new technology good for?). If scholars can now study 10,000 books at a time through a few keystrokes, what deserves their newly empowered attention? If authors can publish for free on KDP, what does that do to the quality of literature?

McGurl, the keynote speaker, is uniquely positioned to speak about the current literary moment. He wrote a widely discussed book, The Program Era (Harvard, 2011), on the proliferation of university creative writing programs in the 20th century and the ways they have influenced American literature.

The rise of Amazon as a literary force, he said, is “foretelling the end of the Program Era.”

“Might the rise of this company represent an inflection point in recent literary history, a place where the state of the art in capitalism is converging with the state of the art in fiction writing?” he said, speaking just a few miles across town from Amazon’s Seattle headquarters.

Amazon’s influence comes largely through its sheer size. The online retailer sold fifty percent of all books in the United States in 2014 and sixty-five percent of all e-books, a market it helped create when it introduced the Kindle e-reader in 2007. The company has acquired an arsenal of services to expand its control over the pipeline from author to reader, including KDP for self-publishing, Kindle Worlds for fan-fiction licensing, Kindle Scout for crowd-sourced discovery of new authors, CreateSpace for print-on-demand books, Audible.com for audio books, and fourteen literary imprints more akin to traditional publishers. It owns the book-theme social networking site Goodreads, which provides the company reams of data on user behavior.

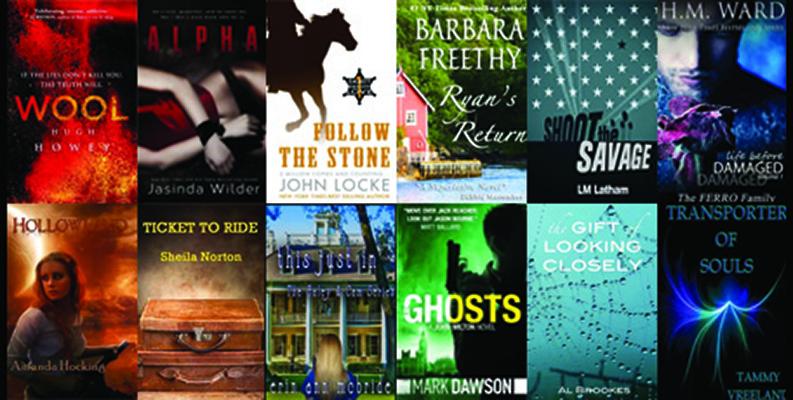

Of the million-plus books self-published through KDP, McGurl has read more than a few. He described the work of Hugh Howey, one of the most successful KDP authors both spurned by and spurning traditional publishers. He praised Howey’s “Stephen King-level talent” and highlighted his debut Wool (2011), as a well-crafted science fiction story with a populist, anti-utopian message. But as readers demanded more in the series, Howey expanded the Wool omnibus, and in ensuing sequels the underlying message essentially flipped, away from its anti-authoritarian roots.

That’s the sort of change we can expect when customer service becomes an artistic imperative. The ban on “disappointing” content, said McGurl, “could be taken to preclude an awful lot of things—including presumably any kind of literature that resists ‘reader enjoyment’ as its ultimate end.”

Wish Fulfillment Centers

The growth of the Kindle universe has brought a surge of genre fiction, including sub-genres like vampire romance and billionaire romance. McGurl described Jasinda Wilder’s bestselling Alpha (2014) series, which begins with a harried young woman struggling with bills, student loan debt, and an ill mother. Mysterious $10,000 checks begin arriving in the mail.

“On some level, the fantasy could stop there,” he said. “There is a real eloquence of duress expressed in the opening chapters of this novel, and, consequently, a great sense of relief when the pressure is off. A helicopter ride, jewels, a blindfold, and what turns out to be an incredibly handsome and well-hung billionaire make things even better.”

Literature as fantasy or wish-fulfillment is nothing new. Long before e-books, authors turned out romances, Westerns, science fiction, and other formulaic types to meet reader demand. But Amazon’s real-time feedback loops amplify the pressure on successful authors to produce more of the same. Through its author sales ranks, it takes commercial pressures that have always been latent in publishing and brings them to a new level of intensity.

“What fascinates me about KDP cultural production is its unoriginality,” McGurl said. “The lack of change is interesting to me. Certainly, Amazon didn’t invent genres. It’s just that when KDP takes it up, what you immediately notice are genres everywhere.”

The Literary Ecosystem

By studying the pipeline from author to publisher to reader, McGurl joins the field of textual studies in examining how books are shaped by cultural and economic systems. In the UW Textual Studies Program, Jeffrey Todd Knight, Associate Professor of English, teaches students that a book is more than a platonic ideal that exists in the mind of an author and gets delivered to the hands of a reader.

“Authors aren’t the only ‘agents of meaning’ in the literary process,” he said. “Publishers, manufacturers, bookstores, agents, readers, and MFA programs all have influence on how texts reach readers, and, by extension, what kind of texts authors produce.”

Knight leads a Simpson Center research group that has explored the Histories and Futures of the Book and the Histories and Futures of Publication. Its theme for the upcoming year, Histories and Futures of Publication, considers Amazon as a prime object of study. To understand how literature became a service, says Knight, look at all the ways Amazon enables reader to add input to the literary marketplace: they can create public reviews, vote for new crowd-funded authors, write Twilight fan fiction, or publish themselves through KDP.

“Readers are being called upon to perform services that feed back into the book’s footprint or prestige, and sometimes even producing writing that goes into the larger textual object,” said Knight. “Every piece of Harry Potter fan fiction becomes part of the Harry Potter enterprise. Those fiction writers are not being compensated for performing a service.”

The Future of Reading

Amazon’s influence has a lot to do with vertical integration: It has become publisher, manufacturer, distributor, bookstore, and reviewer wrapped into one. It doesn’t yet offer an MFA program, but it may be reducing the appeal of them.

“To the extent that the motive for getting an MFA is to become a published novelist, KDP offers a considerably more efficient means to that exulted end,” said McGurl.

In The Program Era, McGurl did more than judge whether MFA programs are good or bad for literature (those debates abound elsewhere). Instead, he offered a nuanced study of how systems of institutional rewards such as scholarships and tenure influence writing. His Amazon lecture, too, focused on the process of influence more than judging the outcome.

In that sense it fit at Scale & Value, which shed light on new questions raised by digital literature and digital text-analysis. Laura Mandell of Texas A&M University argued that large-scale digital analysis risks repeating longstanding biases against women and other groups—unless scholars consider the historical factors that have already kept them out of the literary canon. Richard Jean So and Hoyt Long of the University of Chicago discussed their computational model for identifying stream-of-consciousness writing in digitized books, a method that can work across languages. (They found a rise in stream-of-consciousness novels in Japan after Ulysses was translated.)

The conference was organized by Marshall Brown, Professor of Comparative Literature and Editor of Modern Language Quarterly, Jim English of the University of Pennsylvania, and Ted Underwood of the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

As for what, exactly, the Age of Amazon is doing to the quality of literature, that’s a key question for cultural scholars—and anyone interested in the future of reading. It seems to promise vast new datasets to be studied, perhaps revealing things like the precise life cycles of genres.

“The apocalyptic thing has to stop at some point, doesn’t it?” said McGurl. “And the white billionaire thing?”