Humans don’t have wings because we’ve evolved to be in the world a certain way. We could have evolved a different way. Embracing how we could have been gives us a sense of connectivity with living things, and a sense of how biology works.

The superhero film X-Men: The Last Stand (2006) offers a haunting scene of blood, feathers, and a teenage boy’s pain. With his father pounding on the bathroom door, Warren Worthington III scrapes violently at the wings emerging from his shoulder blades, trying to rid his body of the mutation that will mark him as a social outcast. His father breaks in, and Warren sobs in shame. His desperate attempt to make himself “normal” represents the uncontrollable changes of adolescence. If we don’t all sprout wings, most of us find our bodies surging with new growth, new hormones, and new desires that are impossible at first to understand.

For Phillip Thurtle, the scene is powerful not for what happens to Worthington, but for what never happens to the rest of us: the emergence of wings, and the ability to fly.

Thurtle, a University of Washington historian, has launched a remarkably wide-ranging research project from a seemingly frivolous question: Why don’t humans have wings? The issue doesn’t exactly top research agendas in the same way as developing renewable energy or fighting antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Yet the question, in Thurtle’s hands, is surprisingly useful. By using it as a guide through the history of science and the rise of modern genetics, with a left turn through the arts, he emerges with compelling insights into racial politics, environmental thought, disability studies, and other pressing social concerns.

Thurtle’s digital showcase, Losing My Wings, invites viewers to explore his multifarious argument in whatever order they choose. The landing page presents a human arm skeleton overlaid with a bird-like wing that flickers at the motion of a mouse, suggesting the fluid nature of evolution. From there, tangled pathways open up, embedded with excerpts from the X-Men, The X-Files, fantasy fiction, ancient sculpture, and biology texts. They present a playful mosaic of what Thurtle calls “developmental paths not taken.”

“Humans don’t have wings because we’ve evolved to be in the world a certain way,” he told me. “We could have evolved a different way. Embracing how we could have been gives us a sense of connectivity with living things, and a sense of how biology works.”

‘The Longing in My Shoulders’

For an intellectual venture, Losing My Wings began with a distinctly bodily sensation. Thurtle describes a moment of epiphany while reading China Miéville‘s fantasy novel Perdido Street Station (2000). The character Yagharek is a bird-man, or garuda (a term from Hindu and Buddhist mythology), whose wings have been sawed off as punishment for a crime. “I feel the wind force my fingers apart,” Yagharek reflects. “I am buffeted invitingly. I feel the twitching as my ragged flanges of wingbone stretch.”

As he read the passage, Thurtle felt his own “twitching phantom limbs.”

“Much like Yagharek, I too went through a gothic moment where I lost the potential for flight. I know this through the longing in my shoulders,” he writes on Gothic Wings.

He calls the moment “gothic” for the way it felt charged with spooky, otherworldly consequence. He began noticing how often winged humans appear in pop culture. He thought of the X-Men, Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire, Natalie Portman in Black Swan, the 1958 film The Fly and its multiple remakes, and on. Ancient myths, too, from Icarus to Hanuman, are suffused with stories of heroes gaining and losing the power of flight.

What is it about flight that stirs such powerful feeling? The stories that move us most powerfully, Thurtle considered, don’t create new emotions. They evoke feelings already latent within us.

“Why are some scenes so powerful that they keep coming back to us?” he said. “It’s not just because they’re a metaphor. It’s often because they express something that we are feeling yet lack the words or images to express.”

Genetic Ghost Stories

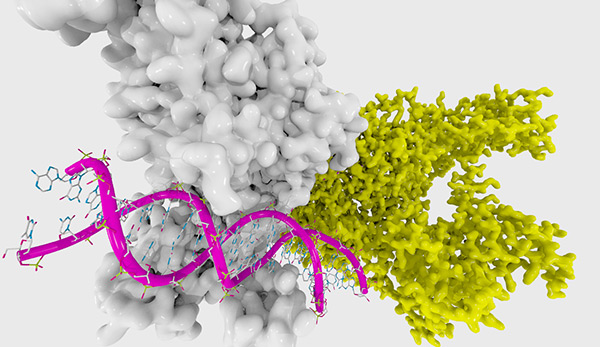

Stories of lost wings brought Thurtle closer to a question arising from modern genetics. One of the field’s key discoveries is the remarkable genetic similarity among species. Human DNA is 99.9 percent identical with each other—and 90 percent with chimpanzees, 85 percent with cows, and 47 percent with fruit flies. How do living creatures turn out so differently when we share so much genetic material?

Advances in genetic mapping suggest that genes function not as predetermined blueprints for building, but as switches that can be flipped on or off for different outcomes. The behavior of genes, not their structure, accounts for differences in form. The same gene that controls bristle development in a fruit fly also controls the color of spots on a butterfly’s wing.

The fast-growing field of epigenetics seeks to understand the exact nature of this regulation. What is it that controls how genes behave? Epigenetics—“above” or “beyond” genetics—suggests there is a layer of something that regulates genes, though vigorous debate swings on the exact mechanism. The field raises new questions about whether genetic changes can be inherited across generations, while dozens of new clinical trials seek to find medical promise in epigenetic drugs.

For Thurtle, the field invites new possibilities for thinking about the way bodies develop. As creatures develop, he reasoned, there are crucial moments when genetic “switches” flip on or off. Bodies sprout wings or they don’t. They grow talons or gills or opposable thumbs, or they don’t. Tails keep growing or stop, leaving vestigial remnants. Thurtle calls these “gothic moments.” They are “haunted by futures that could have been.”

Flights of Connection

The language of “paths not taken” can have a sorrowful tone, as if imagining alternate lives leads chiefly to regret—the lives you might have lived, the lovers you might have loved, the flights you might have flown. Much of the artwork in Gothic Wings reflects a sense of loss, from Yagharek’s longing to Worthington’s fear of leaving childhood for a new life as a mutant.

Yet this sense of isolation is a launchpad for interesting departures. If gothic moments separate us from the creatures we might have been, they also connect us with species who split off on their own developmental pathways. Tracing those lines back, Thurtle suggests, might lead us to a profound new sense of connection with other creatures, human and otherwise. While UW colleagues are approaching animal studies from a postcolonialist perspective, Thurtle arrives at the field through the marriage of gothic literature and evolutionary history.

“This gives us a way of thinking about how bodies are always related in certain ways,” he said. “The only thing that makes us different is certain decision points.”

Wings are a particularly interesting example. In religious mythology, flight often represents humanity’s desire to ascend toward some heavenly divine, away from the confines of earthly bodies. Thurtle wonders if flight could represent an immanent, rather than transcendent, connection. What if it unites us with fellow creatures, winged and otherwise?

“Part of the reason why I chose wings is to displace this moment of transcendence and make it this radical affirmation of immanence,” he said. “Instead of thinking about transcending our human biological condition, we can think about it as an exploration of the biology of humans.”

Digital Playground

Bridging science and the humanities is typical for Thurtle, who studied biochemistry at Evergreen State College and went on to work in a molecular immunology lab. At age 34 he switched tacks and entered Stanford University’s PhD program in the history and philosophy of science. His first book, The Emergence of Genetic Rationality (2007), explains the growth of genetic science as, essentially, an information-management practice, dependent on advances in record-keeping. He co-created a DVD and website, Biofutures (2008), that explored ethical dimensions of new advances in biotechnology. He teaches in the wide-ranging Comparative History of Ideas program at the UW.

Thurtle’s forthcoming book, under contract in the Posthumanities series at the University of Minnesota Press, develops many of the ideas in Gothic Wings. For a project drawing on diverse media, though, he wanted a platform that could display those sources. In 2015 he received a Digital Humanities Summer Fellowship from the UW Simpson Center for the Humanities, which let him explore emerging digital scholarship tools. He arrived at Scalar, a platform developed by the Alliance for Networking Visual Culture at the University of Southern California, which allows for flexible nonlinear storytelling.

That allowed him to pull together a breadth of disparate ideas into a comprehensible package, said Tad Hirsch, an Associate Professor of Interaction Design at the UW and a digital humanities summer colleague.

“While ambitiously scoped, he somehow manages to pull everything together in a coherent, engaging, even playful narrative,” Hirsch said. “While reading his text, I too felt his ‘longing in my shoulders.’”

“This is a really, really smart way to understand the deep logic of contemporary development biology,” said Robert Mitchell, a Duke University professor of English and information science and a collaborator on the Biofutures project. “It is also a way that makes this deep logic accessible to non-biologists.”

Regulating ‘Normal’

In 2012, Thurtle presented “What Superheroes are Made Of,” a TEDx talk on how the nature of heroism changes in a globalized, interconnected world. Instead of self-contained individuals, modern heroes are those who are shaped by their environment—and then draw power from it. Spiderman is bit by a radioactive spider, Hulk is bombarded by gamma rays, Daredevil is transformed by radioactive waste, and Swamp Thing is made entirely of plant material.

“To become a hero, you have to radically open yourself up to the environment around you,” he said. “With great power comes great vulnerability.”

As the X-Men films show, humans tend to regard mutants as threats, even when they’re saving the world. That brings Thurtle back to the notion of regulation. He uses the term to mean not just top-down laws, but the entire social substrate in which we live. Just as genetic regulation determines the shape of bodies, social regulation becomes a powerful metaphor for examining issues of justice.

“When we think about oppression in society, we tend to think about inclusion versus exclusion,” he told me. “Who gets included, who gets excluded. But how you’re regulated, how you are included in society, matters too.”

For example, racial equity in higher education is a question of more than who gets admitted to colleges. It also matters who teaches those students, what texts they read, whether they can afford tuition, who their classmates are, and how they’re treated—all issues confronted by recent campus activism. Black Lives Matter, similarly, understands police brutality as a form of regulation turned deeply dysfunctional.

Environmental crises, too, come down to questions of regulation. The founding text of modern environmentalism, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, tracks the unregulated pesticides that spread from their intended crops into other fields, waterways, lungs, and bloodstreams. Climate change shows how a seemingly innocuous natural gas becomes, without regulation, a dangerous pollutant.

Finally, variance and regulation have great implications for disability studies. Studying disabled bodies in pop-culture history, such as the exploited bodies in circus sideshows, has shown Thurtle that the very idea of “normal” depends on variations.

“There would be no normal without variations,” he said. “There is no way to define when something is normal unless you figure out the variations that created different pathways.”

That means “normal” is not an ideal type. “This gives us a strategy for thinking about why variance is valuable,” he said. “Each of these gothic moments tell us not only about our differences but about our connections.

“Biology works by finding potential. I would like to see society work by opening up potential for all beings. If somebody else has defined your potential for you, they’ve defined you too narrowly.”