“There seems to be a very particular way of talking about guns, on the part of both gun advocates and gun-control advocates … I just intuitively felt like that conversation wasn’t capturing part of the experience of guns for people who find them meaningful.”

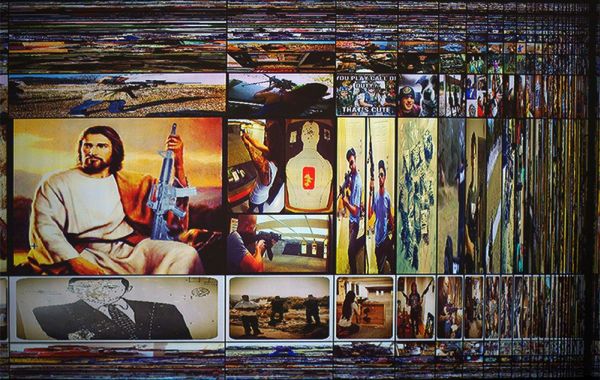

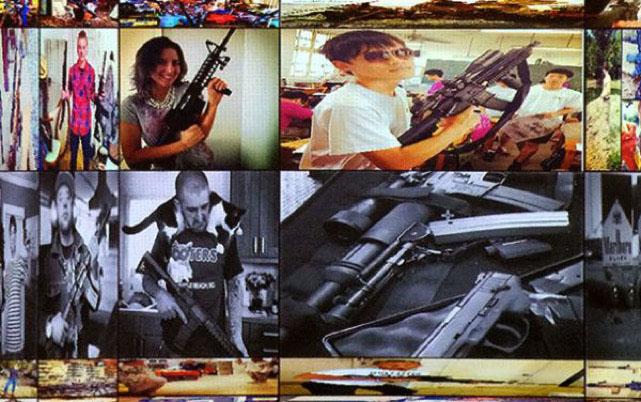

The people holding assault rifles in Tad Hirsch’s recent artwork display them in a staggering array of poses. They aim their weapons in shooting ranges, hunting grounds, and bedrooms. They wear camouflage and gold chains and night-vision goggles. They strike poses from Grand Theft Auto and Call of Duty. They glower and smirk and stare deadpan at the camera. They flex biceps and show cleavage. They display guns beside four-wheelers, beside dogs, and, in a startling number, beside babies.

The common element is the AR-15 semi-automatic rifle, the most popular rifle in the United States.

Hirsch, Assistant Professor of Interaction Design at the University of Washington, wrote a script to pull every image tagged with “#AR15” on Instagram over eight months in 2013. That yielded 79,898 posts. He used face-recognition software and narrowed the set down to 15,000, which he arranged in a digital mosaic titled “A Well-Regulated Militia,” first displayed at the UW’s Jacob Lawrence Gallery in fall 2015. Viewers navigate the screen with a fish-eye distortion lens, mousing across to make images rise and recede in a sea of selfies.

The effect is potent. I went to see Hirsch’s exhibit hoping for a moment of empathetic connection. I expected to find that gun selfies are just one more flavor of social-media performance. Whether we pose to show off our guns or clothes or kids or latte art or whatever, we’re all trying to say Look at me, I’m having fun, I’m strong, funny, beautiful, lovable, and on.

But that’s not what I found. Hirsch’s installation made clear that semi-automatic rifles are not neutral objects but “contentious products,” in his words. They are instruments of death. The AR-15 was used in the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, the 2012 Aurora, Colorado shooting, the 2015 San Bernardino Shooting, and many other mass shootings. That fact shapes how I view the photos—how many people view the AR-15. The faces in Hirsch’s mosaic carry an undercurrent of aggression or belligerence or raging against the President. Others exude simple glee at doing something transgressive—something that will piss off liberals. Finding empathy was more difficult than I expected.

That difficulty is what first drew Hirsch to examine the “Instagram militia,” as AR-15 owners on the app are known. After the Sandy Hook shooting and the subsequent failure of Congress to pass even modest gun-control legislation, he felt the public debate was missing something about the everyday lived experience of gun owners.

“There seems to be a very particular way of talking about guns, on the part of both gun advocates and gun-control advocates,” he said. “It seems like a very narrow discussion. Not knowing anything about guns or the people who love them, I just intuitively felt like that conversation wasn’t capturing part of the experience of guns for people who find them meaningful.”

At the same time, his son, then five, was growing fascinated with guns. “I was trying to understand what he sees in them,” Hirsch said. “In some ways I get it. I was like that at eight years old, but in other ways I was really struggling.”

America’s Gun

The mosaic is part of Hirsch’s broader study of US gun culture, a project that straddles art, design, and scholarly analysis. He draws on his previous work as a programmer—before coming to the UW he was a research scientist at Intel Labs and Motorola’s Advanced Concepts Group. He manipulates the Instagram dataset on multiple levels, sorting images and their captions, comments, and location information in search of patterns. His project, supported by a Digital Humanities Summer Fellowship from the Simpson Center for the Humanities in 2015, is titled “Field-Stripping America’s Rifle.” Just as a soldier or hunter dissembles a complex weapon to examine its components, Hirsch wants to peel back the layers of performance involved in gun selfies.

“I’m really interested in the question of how to do public engagement around the gun question,” he said. “How do you do it in a way that’s not just about disseminating information, but in a way that creates some kind of encounter with the artifacts of culture?”

His gun research quickly brought him to the AR-15, the civilian version of the military M-16, nicknamed “America’s gun.” There are millions in circulation in the US. “It’s the one that makes gun-control advocates craziest,” Hirsch said. “It’s the hardest one to justify.”

Because Craigslist bans gun sales, Instagram has become a de facto gun market, largely unregulated (its parent company, Facebook, has taken some steps to restrict gun sales). The site includes thousands of images of AR-15 ammunition clips, scopes, grips, night vision devices, laser-targeting devices, sound suppressors, and other accessories. The AR-15’s modular design, with a core platform to which users attach components, makes the possibilities for accessorizing essentially endless. The gun has been called “Legos for grown-ups” and a “Barbie doll for guys.”

As Hirsch sorted his images by color, he found clusters of bright pink accessories, suggesting a gendered dimension to AR-15 culture. Another cluster gathered the blocky white text of social-media memes. Camouflage clothing clustered together, as did black Mafioso suits. Hirsch grew interested in the different tropes that Instagram users emulate in their clothing and posture—militarized “black ops” poses, gangsta-rap poses, white-collar Grand Theft Autoposes, and paintball and airsoft poses.

As he worked with other digital humanities faculty at the Simpson Center, Hirsch discovered parallels to the rise of “distant reading” that literary scholars use to analyze large bodies of text. Like algorithmic textual analysis, Hirsch’s visual analysis is an experiment in method for the scholar. It also opens up new paths of exploration for viewers, who do their own navigation.

“Instead of closing down the possibilities for inquiry, Tad has developed interfaces that facilitate the viewer's interpretive engagement with the data,” said Luke Bergmann (Geography), another fellow in the 2015 digital humanities program.

Sales Pitches

In a preliminary finding, Hirsch said there seems to be a strong correlation between posts invoking Second-Amendment language of liberty and images promoting gun commerce. In other words, such language may be less about values than a sales pitch. But Hirsch is less interested in pushing conclusions than in creating space for viewers to do their own interpretation.

“I want to create situations where people can

He has further exhibits along with publishing projects in the works. In “Seattle City Bang-Bang,” a companion piece at the Jacob Lawrence Gallery last fall, a small box was mounted on a wall. Each time a gunshot was recorded in Seattle police logs, a loud audible shot rang out in the gallery. The box also emitted a paper ticker, like a receipt printer, with the shot’s date, time, and location. Within a few weeks a 15-foot paper trail crept across the floor, forcing visitors to step around it. Where crime maps make it easy to imagine gun violence as an isolated problem in “problem neighborhoods,” the ticker and audible shots suggest they are everyone’s problem, Hirsch said. The ticker's bureaucratic tone also suggests the role of public policy in creating concentrated violence.

Scott Lawrimore, director of the gallery, watched visitors react to both pieces. As the images flew by on a projection screen, viewers shook their heads in shock or laughed, another way of dealing with disturbing material.

“The piece is troubling,” he said. “To see how proud people are of those guns . . . That gun is designed to do one thing, which is kill people, and kill a lot of them. It represents some of the worst aspects of our humanity.”

Empathy and Selfies

As I navigated the screen, it was hard to avoid the conclusion that AR-15s represent a form of power to a class of Americans who feel passed by in a multicultural-globalized-gilded-wealth world. They “cling to guns or religion,” in Barack Obama’s infamous formulation from a private fundraiser in 2008.

Hirsch’s mosaic reveals, I think, the limited ability of social media to promote empathy. Great stories, like great photographs and other artwork (not to mention face-to-face conversation) can create lines of connection between people who think they have none. That possibility is severely diminished in the endless procession of selfies we get on Instagram and other social media. Yet empathy is precisely what we need on these sites where so much of our public discourse has moved.

Hirsch’s project brings viewers eye-level with faces that resist easy connection. In doing so, it demonstrates the insufficiency of, in writer Ta-Nehisi Coates’ words, “a soft, flattering, hand-holding empathy,” the sort meant to make us feel better without any honest reckoning of our most difficult divisions. It nudges us toward what Coates calls “a muscular empathy,” rooted in curiosity and developed through education.

Such work requires more than looking at selfies. By exposing the limitations of such images, Hirsch makes a powerful case for looking beyond them.