“The great victories that have been won recently in marriage equality and other federal laws were possible only because of the generations of activism and the breakthroughs in local laws that came before."

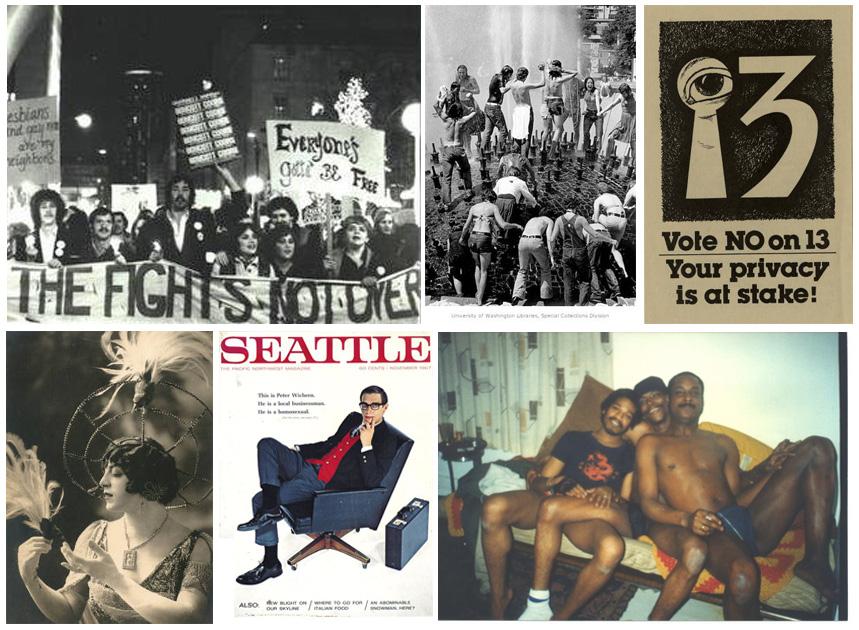

The images of the LGBTQ Activism in Seattle History Project stand in stark contrast with each other. In one, marchers carry a banner proclaiming “The Fight’s Not Over,” claiming their place in the broader civil rights struggle. In another, barely-dressed members of the group Black and White Men Together lie together on a sofa, grinning in a defiant, playful display of sexuality and fraternity.

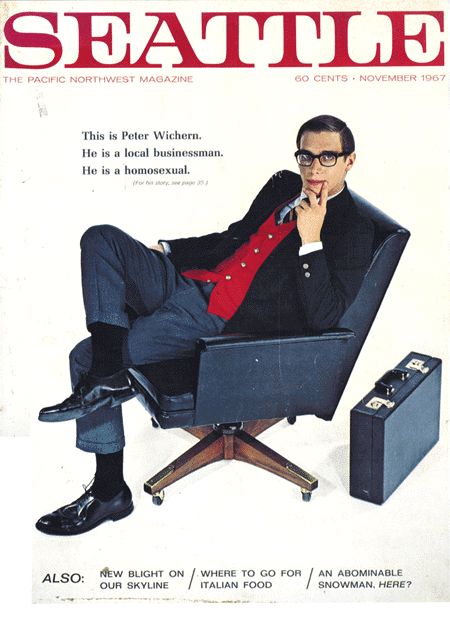

The image that seized my attention is a 1967 Seattle magazine cover. A nattily dressed man with sport coat and briefcase sits in an executive chair, straight from Mad Men casting. The accompanying text reads:

This is Peter Wichern.

He is a local businessman.

He is a homosexual.

In the accompanying article, Wichern contrasted his younger days "in the bars all the time ... like someone possessed by demons" with the middle-class life he was trying to maintain. In one sense, it’s a classic example of so-called respectability politics—the notion that oppressed minorities can gain acceptance by “fitting in” to the dominant culture. It’s a mistaken strategy because it doesn’t require people who are doing the oppressing to change.

The photo was also a courageous act. Coming out in public was “virtually unprecedented” at the time, the magazine notes. Wichern, the 21-year-old son of a Montana preacher, was the only member of a newly formed gay-rights organization, the Dorian Society, willing to give his real name.

Together with the other images, Wichern’s photo shows the diverse strategies that LGBTQ people used to demand rights in a culture that had never considered them equals. More than that, they demonstrate the vast effort that Seattle activists have made to achieve those rights—pushing the nation forward in the process.

Those efforts are preserved in the new LGBTQ Activism in Seattle History Project website, a collection of essays, photos, oral history videos, a timeline, and an organizational catalog at the University of Washington. It’s the latest arm of the expansive Pacific Northwest Labor and Civil Rights Projects, a series led by UW History Professor Jim Gregory that has drawn more than 6 million page views. Earlier sections of the site exposed racist housing covenants in Seattle neighborhoods, leading to state legislation to remove them. A related site chronicles the political battles leading to the SeaTac and Seattle $15 minimum wage victories.

The new site shows how local activism can eventually grow into nationwide progress, Gregory said.

“The great victories that have been won recently in marriage equality and other federal laws were possible only because of the generations of activism and the breakthroughs in local laws that came before,” he said.

Privacy vs. Pride Politics

The new project, led by Kevin McKenna, a UW doctoral student in history, tracks how the city evolved from a 19th-century boomtown into the pioneer of some of the nation’s first nondiscrimination laws. In the male-dominated gold rush days, homosexual activity was common, though anything resembling gay culture was decades from emerging. The state passed an anti-sodomy law in 1893; the site includes an indictment from the same year. Breaking the law could result in sentences twice as long as for heterosexual rape, according to an essay on the site by McKenna and Michael Aguirre, another history doctoral student.

As with other cities, industrialization created an urban refuge where men, women, and trans people could escape the scrutiny of smaller communities. As gay bars emerged in Seattle, they arranged bribery payoffs with police, avoiding the Stonewall-types raids of places like New York and San Francisco.

The Dorian Society, in 1967, became the city’s first gay-rights organization, opening a community center on Capitol Hill that provided counseling services and employment help. In 1973 the city council passed an employment nondiscrimination law protecting sexual minorities, and in 1975 it passed a housing nondiscrimination law, two of the first such laws in the nation.

In 1978, a crucial battle arose over a ballot initiative that would have overturned those laws. Such measures had recently passed in Miami-Dade County; St. Paul, Minnesota; Wichita, Kansas; and Eugene, Oregon. With Initiative 13, Seattle voters became the first to defeat such a measure, affirming their city’s equal-rights policy.

That campaign exposed cultural and strategic divisions among LGBTQ groups. Some embraced the rainbows, leather, and drag of the emerging pride politics, while others pursued the buttoned-down look of the earlier Dorian Society. In their messaging, some groups downplayed the issue of gay rights by emphasizing privacy instead.

“Their strategy was to make the campaign not about gay rights but about universal right to privacy,” McKenna said. “The theory was that there was enough anti-gay sentiment to defeat it.

“On the other side were gay men and lesbian women who saw this as a chance to educate the public about what it means to be a sexual minority. They said, ‘If you take away our rights, what’s to stop them from taking away the rights of black people or other minorities?’”

The defeat-13 campaign succeeded by a nearly two-to-one margin, including strong support in the African-American Central District.

A Diverse Coalition

The project also charts differences within the LGBTQ world, noting white privilege and conflicts between hyper-masculine gay men and other groups, a tension that surfaced in the 1980 Lesbian and Gay Pride March. The oral history interviews show the diversity of backgrounds within the movement. In one, Yolanda Alaniz speaks about confronting sexism among Chicano activists. In another, Marsha Botzer speaks about founding the Ingersoll Gender Center in Seattle in 1979, the nation’s first transgender activism and community center.

One of McKenna’s favorite parts of the site is a catalog of organizations that reflects the diversity of the movement. It describes group like Pride Asia, Emerald City Black Pride, and Noor, for LGBTQ people who have ever identified as Muslim. It also provides information for joining them.

“I want the site to be—and I hope it further becomes—as inclusive as possible,” McKenna said. “There are a lot of different issues within what is called the LBGTQ community that are in tension with each other. It’s important to me that they’re all represented.”

Creating a site for the public forced McKenna to think differently than in writing his dissertation, which examines the intersection of sexual civil rights and pro-business politics in Seattle. “Ultimately, this project is accountable to the community in a way that my dissertation isn’t,” he said.

Conducting oral histories brought differing interpretations of how change happened and which political strategies worked, he said. That experience forced him to present information without giving undue credence to one perspective over the others.

McKenna hopes the site brings awareness of the work remaining.

“Queer youth continue to face disproportionate rates of homelessness, mental health issues, and domestic violence, and trans people are far more likely to live in poverty than cisgender people,” he writes.

“There are still a lot of gay, trans, and queer youth getting kicked out of their homes,” he said. “Not everyone is as accepting as we like to think.”

Blind Spots Past and Present

The Peter Wichern cover made me curious about the Seattle magazine of November 1967, which I found in the Suzzallo Library stacks. In the cover story on “The Homosexual in Seattle,” reporter Ruth Wolf does her best to synthesize current research. I could relate to that effort, even if the research available to her was woefully wrong: “Today the most generally accepted view is that homosexuality has its roots in the family constellation—that it results from an abnormal relationship with one or both parents.”

She describes her visit with the Dorian Society, a group that banned dressing in drag in hopes of presenting a more acceptable image of gay lifestyle. She notes, “There were no limp wrists, no girlish giggles.”

I’m sure she imagined that to be a telling, humanizing detail—even as we recognize it now as a hurtful stereotype. In the same way, I am surely reflecting the blind spots of my own era, in ways that are unknown to me. History cannot reveal those blind spots in advance, but it can give us humility that we are no more free of ignorance than our predecessors.

The Northwest Lesbian and Gay History Museum Project, which partnered with the UW project and shared materials, has an interview with Peter Wichern’s partner, Louis Giguere, conducted after Wichern had died. He said Wichern’s life as a Seattle businessman was much less sanguine than the cover suggested.

“Well, the reality is, Peter was struggling with the business that was floundering off and on,” Giguere said. “He was out drinking in the evenings and partying. This picture, while it looks nice for the cover—it wasn't him.”

Later, Wichern moved to the Bay Area and worked for the software company Oracle. He joined the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and helped lead a campaign for domestic-partner benefits in corporations—an unusual concept in the 1980s.

“He finally came to the conclusion that you don't change the world by screaming and yelling and throwing red paint at people,” his partner said. “You change the world by going into the corporate dragon's den and changing the way money is spent, because money is what makes the world go 'round.”

Petitioning for corporate benefits became one more strategy for change. It worked alongside Civil Rights demonstrations, flamboyant pride expressions, appeals to respectability and privacy, and other forms of activism. Those methods sometimes stand in tension with each other. Yet they can unite, eventually, like a mighty stream, even when the way forward is unclear.

The LGBTQ Activism in Seattle History Project is supported by the Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest, the Department of History, UW Libraries, and King County 4Culture. The Simpson Center for the Humanities co-sponsored the October 2016 launch of the project and has supported earlier versions of the Pacific Northwest Labor and Civil Rights Projects. In 2015, the Simpson Center awarded Jim Gregory the Barclay Simpson Prize for Scholarship in Public.