It’s about the co-creation of social space within the context of social inequality. We recognize inequality, we don’t pretend it’s not there, and we still engage with each other.

When the indie-rock band Girl in a Coma visited a museum in San Antonio in 2009, they found themselves included in the exhibition. The museum was featuring American Sabor, a bi-lingual celebration of the contributions of Latinas and Latinos to US pop music.

Michelle Habell-Pallán, a co-organizer and a cultural studies scholar at the University of Washington, helped the exhibition trace the rich streams of Latin jazz, soul, and rock, from the Cuban roots of “Louie Louie” to the Los Angeles punk. She also included a shout-out to Girl in a Coma, a band of three San Antonio women who turned their Tejano heritage into a raucous, feminist sound. Seeing themselves reflected at the Museo Alamedo, the band tweeted “Super proud.”

The band’s music shares American Sabor’s expansive quality. In “Clumsy Sky,” singer and guitarist Nina Diaz gestures toward an alternate world where divisions dissolve into joyful noise: “Picture me away … Something’s gonna happen … we are the stars that light up the night.”

The music video does a bit of historical archiving as well, documenting Lerma’s Night Club, a beloved, threatened San Antonio landmark. The end of the video shows Girl in a Coma alongside photos of revered (and all-male) conjunto bands, claiming their place in the region’s musical pantheon.

In a new book project, Habell-Pallán dwells on the “away” that Girl in a Coma evokes in “Clumsy Sky.” To her, it signals an image of chicanafuturism, a de-colonial vision of alternate pasts that transform injustice and give way to social and cultural flourishing.

She also considers the feedback that rings from Diaz’s guitar, through her amplifier, and back into the guitar. The technique—used by rockers from Jimi Hendrix to Prince to Carlos Santana—suggests a model for the fertile interplay of artists, scholars, community members, and institutions like museums.

Working together, they can amplify and modify each other’s work, creating something altogether new.

To Habell-Pallán, that offered a potent metaphor for the possibilities of public scholarship, a philosophy that has marked her career through a series of groundbreaking projects, including American Sabor and the oral history project Women Who Rock: Making Scenes, Building Communities.

As the new director of the University of Washington’s graduate Certificate in Public Scholarship, Habell-Pallán, Associate Professor of Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies, will share such possibilities with students.

“It’s an exciting moment in the university,” she said. “We’re lucky to have the resources we have in terms of faculty with experience. We’re also rich in graduate students who want to do this sort of work and in communities that are willing to invest their time and energy to engage with us.”

A Growing Cohort

The Certificate in Public Scholarship, a 15-credit graduate program structured around portfolio- and project-based work, lets UW graduate students develop skills in community-engaged research, teaching, and service. It was incubated at the Simpson Center for the Humanities, enrolled its first cohort in 2010, and is now a partnership of the Simpson Center, the Graduate School, and the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences (IAS) at UW Bothell.

IAS Dean Bruce Burgett, the certificate’s inaugural co-founder with Miriam Bartha, praised Habell-Pallán’s record in publicly engaged projects and her work as a portfolio advisor and a steering committee member for the certificate.

“The certificate’s ongoing sustainability and development needs regular infusions of new leadership,” he said. “We are excited for the new energy, ideas, and connections that Michelle brings to her role.”

Bartha, Director of IAS Graduate Programs, will continue as the certificate’s Graduate Program Advisor and administrative lead.

The certificate arose from national conversations about the need to form more socially engaged scholarly practices and mutually beneficial partnerships among campuses and communities. In 2016, the steering committee revised its learning objectives to explicitly welcome scholarship that seeks social equity, access, and inclusion as a response to historical injustice.

Six years in, the certificate has a growing cohort of alumni with successful portfolios and practicum projects. Habell-Pallán points to Queering the Museum, a multimedia project led by Nicole Robert (Gender, Women, & Sexuality Studies), and supervised by Ron Krabill (Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences, UW Bothell), which explores the role that museums play in forming gender and sexuality norms. The project led to an exhibit, Revealing Queer, that ran for five months at Seattle’s Museum of History and Industry.

Habell-Pallán also praises the Chicana/o Radio Archive project of Monica De La Torre (Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies), supervised by John Vallier (UW Libraries), which contributed to De La Torre’s hire as Assistant Professor in Media & Expressive Culture at Arizona State University.

Amy Piedalue (Geography), now a post-doctoral fellow with the Australia India Institute at the University of Melbourne, modeled her practicum as community-based participatory research with the Peaceful Families Task Force of API Chaya, a sexual and domestic violence organization. Piedalue co-published her work with API Chaya research partners Farah Abdul and Sarah Rizvi.

As director, Habell-Pallán will work to keep coursework and portfolio work flexible, allowing students to bring preexisting relationships and projects into the program. She will encourage faculty to help identify courses that can count toward the certificate. She will also advocate for public scholarship across academic departments.

“We need understanding in students’ home departments and committees about the value of this work, even though it may not be in traditional print form,” she said. “There are ways to design and deliver rigorous scholarship through new and unconventional platforms.”

(The certificate invites campus and community members to a Fiesta Pública y Critica—a series of informal conversations on justice and scholarship—on Wednesday, February 22.)

Rocking the Archive

Habell-Pallán grew up in a Southern California neighborhood in the process of becoming ethnically diverse, and not always peacefully so. The racial slurs she sometimes heard as a teenager made discovering punk music all the more welcoming.

Habell-Pallán grew up in a Southern California neighborhood in the process of becoming ethnically diverse, and not always peacefully so. The racial slurs she sometimes heard as a teenager made discovering punk music all the more welcoming.

“Punk music was appealing to me because it’s a way to say ‘It’s all right to be a misfit and an outsider,’” she said. As one of the few Mexican-American students in majority white high-school, she found in punk “an ethic that cares about people rather than marginalizing them and treating them terribly based on their skin color. And a language to speak back to teachers who justified social inequality.”

As an MA student at the University of California, San Diego, and as a doctoral student at the University of California, Santa Cruz, she made the case for unconventional research into L.A.’s grassroots feminist and queer music. She describes the origins of her career as “a conventional cultural studies scholar,” leading to her books Loca Motion: The Travels of Chicana and Latina Popular Culture (2005), Cornbread and Cuchifritos: Ethnic Identity Politics, Transnationalization, and Transculturation in American Urban Popular Music (co-edited with William Raussert, 2011), and Latina/o Popular Culture (co-edited with Mary Romero, 2002).

In 2003, the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation and the newly formed Experience Music Project (EMP) funded a UW collaboration grant. Habell-Pallán, Shannon Dudley (Ethnomusicology, School of Music), Marisol Berríos-Miranda (Ethnomusicology, School of Music), and graduate students Rob Carrol and Francisco Orozco, saw the potential for the seeds of American Sabor. Over a series of iterations, they found collaborators at the radio station KEXP, the Simpson Center, the Smithsonian Institution, and elsewhere.

Working with museum curators taught Habell-Pallán about balancing the needs of different audiences. Where scholars prize thoroughness and precision, many museums require text written at an 8th-grade level. When Habell-Pallán offered cultural context, curators urged her to let the music speak for itself. There were disagreements, but they ultimately found a path forward. The EMP exhibit grew into a traveling Smithsonian exhibition, which Girl in a Coma found in San Antonio. A book from American Sabor, bilingual and geared toward a broad audience, is in press with the University of Washington Press, co-authored by Habell-Pallán, Dudley, and Berríos-Miranda.

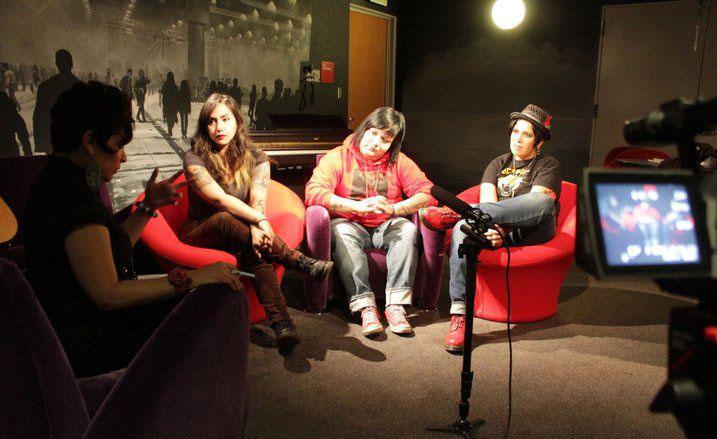

Later, Habell-Pallán and Sonnet Retman (American Ethnic Studies) helped develop Women Who Rock, an oral history archive and series of public “unconferences” documenting women who use pop music as a tool for social transformation. Like Girl in a Coma’s anthems, Women Who Rock participants “rock the archive” by claiming a place for women musicians, DJs, critics, fans, and others in the male-dominated narrative of rock ‘n’ roll history. The group invites participants to its annual gathering on Saturday, February 11.

An Ethic of Relationality

Such work has led Habell-Pallán to see an ethic of relationality (or relationship) as the core of public scholarship. Another partnership, the Seattle Fandango Project, uses music, dance, and verse to create a space of “convivencia,” or co-living (co-vivir) as a stage for social-justice work.

The closest English word, conviviality, doesn’t quite capture the sense of building trust through time together.

“It’s about the co-creation of social space within the context of social inequality,” Habell-Pallán said. “We recognize inequality, we don’t pretend it’s not there, and we still engage with each other.”

Convivencia offers a model for public scholarship in which scholars can work across boundaries of race/ethnicity, gender, wealth, and access, she said. Collaborators on all sides must work to undo false assumptions—about universities, about under-resourced neighborhoods, and on.

“Part of being a public scholar means understanding that you’re working with different people and organizations with different missions,” she said.

She takes inspiration from the late Stuart Hall, a Jamaica-born cultural theorist who collaborated with filmmakers and spoke to scholarly and public audiences alike, expanding the scope of cultural studies beyond academic audiences.

“Public scholarship means acting as a bridge with the intent of generating something transformative,” Habell-Pallán said. “We’re not here to drop knowledge through a one-way conversation. We’re here to share and learn from each other.”