In order to address issues of power and difference, I utilize metacognition primarily. I use certain activities to situate my students’ individual knowledges, and then have them assess the power dynamics of their having or not having had access to that knowledge. Before teaching a specific topic, I ask students to account for: 1) what they already know; 2) what they don’t know; and, 3) where they got their information from.

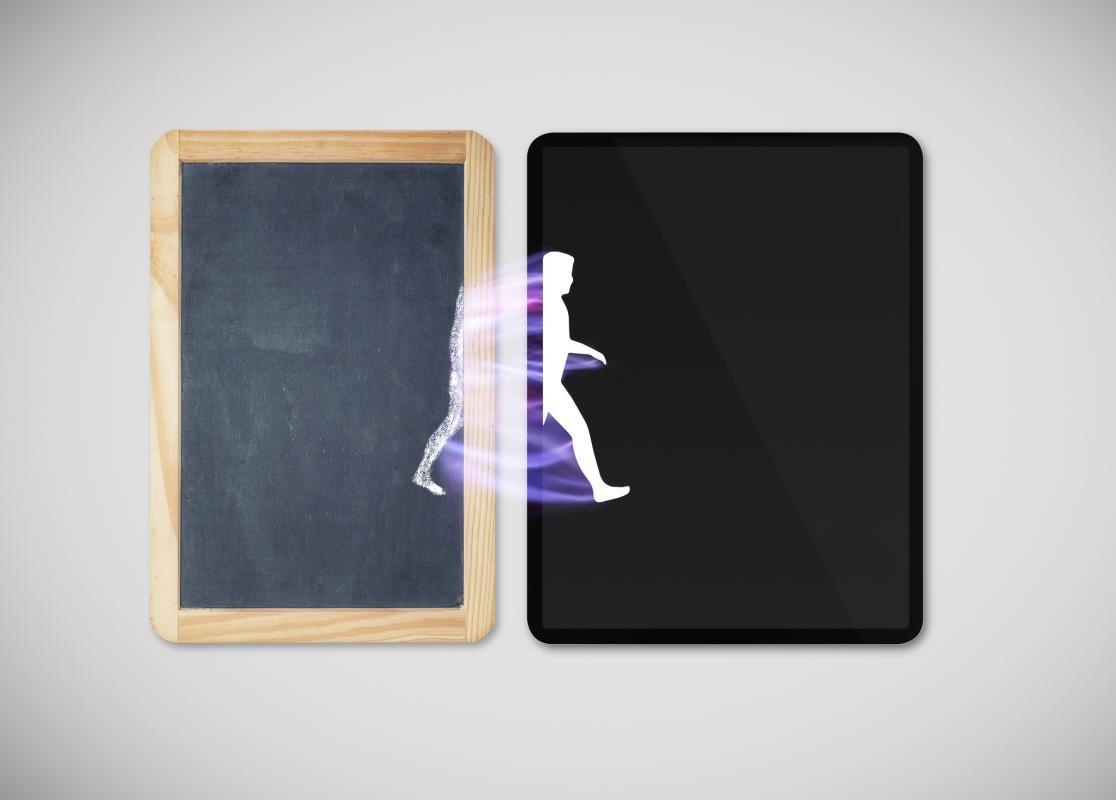

Welcome to Virtual Pedagogies, a regular series in which we ask UW faculty to share their experiences with a particular aspect of teaching online. While there have been a lot of resources that walk through the technicalities of remote teaching, we were hoping to create a space where faculty can share pedagogical approaches. As we’ve all learned quite quickly, what worked in the classroom, doesn’t necessarily work in Zoom.

For this installment, we asked Simpson Center-affiliated scholars how they were ensuring equity and access in their online classrooms. Here’s how they answered:

Alan Michael Weatherford, Former Mellon Summer Fellow in Public Scholarship, PhD Candidate in Cinema & Media Studies:

In order to address issues of power and difference, I utilize metacognition primarily. I use certain activities to situate my students’ individual knowledges, and then have them assess the power dynamics of their having or not having had access to that knowledge. Before teaching a specific topic, I ask students to account for: 1) what they already know; 2) what they don’t know; and, 3) where they got their information from. You can do this in a variety of ways: homework before class, a three-minute reflective write up, small-groups, or a Q&A poll divided up by question. I then do small-group discussions on our access to those knowledges and reflect on if those knowledges were dominant or shut out.

In order to mitigate differential access to my class, I do a few solid things. Generally speaking, I found ways to make sure my students did not have to pay for any of their materials for the course. This may take some planning beforehand; working with a librarian is key. Secondly, Powerpoint Version 16 (maybe even earlier) allows for real-time transcription as you talk and move through your slides. This is ideal for when you’re screen-sharing over zoom.

Joanne Woiak, Co-organizer of Exploring the Fault Lines in Disability Studies, Disability Studies Lecturer, along with "Introduction to Disability Studies" Teaching Assistants Shixin Huang (JSIS PhD Candidate) and Ronnie Thibault (iPhD Candidate):

In disability studies (DS), course content and pedagogy are inseparable. Centering disability as a lived experience and framework for analysis involves attending to the role of disability in the classroom. Many of the methods we typically use to improve accessibility for disabled students also support all of our students. This was true to an even greater extent when our 90-student Introduction to DS course went online. Students rotate as official note-takers for a day, creating documentation of lecture details and discussion topics that everyone can use; extensions and other modifications to assignments are offered universally; and lecture slides and recordings are always available to all. One example of how real-life accessibility practice became an invaluable learning experience was a day when ASL interpreters arrived late owing to technical snafus, and the section group waited for them so that everyone could participate. A couple weeks later we watched a film* where disability activists were adamant that all present would have an opportunity to participate and that no communication would take place unless an interpreter was present.

The main access and equity consideration we had was that students would likely not have equal resources or time to participate in class. We pre-record lectures (which also gives time for our captioner to do her work) and have quiz sections meet synchronously. The TAs hit upon the idea of taking advantage of the online format to break up the students into 10 smaller quiz sections and survey them for the best time of day to meet. This has added to the TA teaching workload, but paid off as student assignments show great comprehension and we find responding to students using chat, emoticons, and the intimate nature of the small classes quicker and more beneficial. Sections are nurtured as community through co-created “classroom” culture, discussion inputs from both TA and students, communal spaces of a Canvas group homepage and Google document, and other practices that value students’ participation and accountability.

Telework and online instructional methods will likely change the landscape for disabled and nondisabled people going forward. The disability community expresses frustration that the kinds of tools and flexible scheduling that they were previously told were infeasible accommodations are now suddenly and routinely made available so that nondisabled people can maintain access to school and work productivity. But specific access needs may also arise in accommodating remote participation. Automatic audio transcript functions are somewhat useful—especially when we edit the “craptions”—but a captioner or ASL interpreter is needed to make content accessible. Meaningful access also involves more than legal compliance. We welcome individual students to contact us any time about what they need and what aspects of our teaching are not working for them. Disability is more than an “add-on” category in considering diversity and equity. DS ways of thinking about and practicing accessibility challenge academia’s myth of normalcy and value different embodied and enminded knowledge within our communities of learners and instructors.

*The film we mention—and recommend as a fantastic primer on disability studies, rights, and accessibility—is Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution (Netflix, 2020).